OPEN SYNTHWAVE

Written By Life Patterns and Jonny Fallout [Photo: by Joseph Pearson on Unsplash]

On Music, Openness, and Innovation

Music innovation is moving at a fever pace — whether it’s the evolution of delivery systems, the software for creating music, or the business models that are being broken even as they’re being made. In fact, music may be the creative industry most disrupted by the digital revolution. We have tremendous power, as artists, at our fingertips now from DAWs to software instruments from distribution platforms to media channels. But the ways in which we work are often still stuck in the 20th century. This is not unusual, of course. It takes a long time for industries to adopt new tools and ways of thinking. And, we’re in the middle of music industry upheaval.

So, where do we go to discover new ways of thinking and working? A familiar quote from cyberpunk godfather William Gibson, is that “the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.” Cross-pollination is a powerful technique for stimulating innovation — taking ideas from one area of creative endeavor and applying them to others. In borrowing techniques from other industries, we can reap their benefits. And one of the most powerful ideas driving innovation in software, science, and a host of others is open source. Open work can speed creation. Sharing can generate not just new ideas but also build community.

So, what does it mean to be open? In the world of software, open source means that the underlying code is available to modify, build upon, and share freely. For instance, the foundational tech protocols that underpin the Web, like HTTP, are open source. In the practice of open science, knowledge, from data to materials to code, is shared through collaborative networks with the purpose of improving the efficiency and increasing the reproducibility of scientific research. Game developers have long understood the power in open development, baring the creative process for all to see. John Carmack used an early Internet protocol to share a daily log of tasks, along with snippets of code, opinion pieces and observations. Complete archives are available online to this day, including on GitHub. Crowdfunded games like Broken Age had notoriously open development cycles, with fans being given access to regular updates and insight into the process.

Opensource.com discusses the open approach to creative work in this way:

“The term originated in the context of software development to designate a specific approach to creating computer programs. Today, however, "open source" designates a broader set of values—what we call "the open source way." Open source projects, products, or initiatives embrace and celebrate principles of open exchange, collaborative participation, rapid prototyping, transparency, meritocracy, and community-oriented development.”

In a lot of important ways, music already has the underpinnings of open source: the melodies, the traditions, the theory, the culture are all part of a framework, an expansive vocabulary that we build on as our starting point. In retrowave and related genres, that vocabulary also includes the sounds, riffs, musical references and atmosphere of the ‘80s.

We can see elements of openness across the music industry, particularly in remixes, mashups, and sampling that permeates dance music and hip hop culture. For example, in 2015, Converse (yes, the famed sneaker company) introduced Rubber Tracks Sample Library — no cost, royalty free loops recorded by various bands and musicians at their Brooklyn, NY studio — and encouraged artists to build the loops into songs. Well-known electronic acts like RJD2 and Com Truise as well as a host of producers, DJs, and electronic musicians participated in the project, which while clearly a marketing effort for Converse, was also an interesting experiment in community building and collaborative digital music making.

Artists across genres have incorporated open practice into their music to build community. Trent Reznor famously made the tracks and stems for his Nine Inch Nails album, “The Slip” and “Year Zero” available for other artists to remix under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 US) license. Premiere synthwave band, The Midnight, offers stems of their songs for use in remixes, in a non-commercial context. And, Berlin-based indie synthwave artist, Neon Deflector, publishes his music under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license which allows other artists to share and adapt his tracks, like this one, “Outpost X”, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as the appropriate credit is given. “Once you create something original, that work is automatically protected by law. By using a Creative Commons license, you don't take away your legal rights or ownership — it remains your property. However, with a license, you can grant permissions to use the intellectual property in specific ways,” Neon Deflector explains.

Trent Reznor made the tracks and stems for his Nine Inch Nails album, “The Slip” available to remix under a Creative Commons license.

Neon Deflector describes some of the reasons he releases his music with an open license and the reach it has given him: “My songs have been used in a variety of ways so far. It's a wonderful feeling to listen to your own sounds in a big SpaceX documentary, as background music to discussions about meme origins, or even in videos about sports cars and urban buildings around the world. The songs thus gain a dimension that I could never have achieved myself. I regularly get comments and positive feedback on my music because someone in this world has used it in the context of their video,” he says.

“I think that above all, you should be aware that once a license has been granted, it cannot be taken back. So if the next movie blockbuster makes millions while your music is playing — don't get angry about it (not that that would ever be a real scenario for me...), but enjoy the reach you achieved.”

“Overall, my music — no matter how it is licensed and used — will always be my music. It's my feelings, my thoughts and it's my work. If a license helps me reach more listeners and gives the songs a life of their own — then that's an asset I love.”

Open Synthwave Concepts

The underpinnings of openness are already present in digital music and culture, but to build new ways of working that extend beyond experimentation into common practice, we’ll need to draw upon and build on the tenets that support open source in other fields.

Open source is powerful because:

It’s distributed and easy to find

It’s battle-tested by thousands, sometimes millions of people

It’s constantly revised and improved upon by the people that use it the most

It can be copied, changed, re-shaped and re-shared by anyone

Open synthwave, then, would operate by sharing both the accumulated knowledge of processes and tools, and the building blocks that can be reused, re-shaped.

Sharing Your Knowledge

Musicians love to talk about their craft. Ask anyone that’s ever approached one with questions about their process, gear or software. However, the ways in which this knowledge is shared tend to be either ad-hoc or monetized. There’s nothing inherently wrong with either approach, but they don’t lend themselves to the type of collaboration that thrives in software development.

So, how do you share that knowledge? Social media is a powerful tool for engaging with peers in a public forum. Knowledge is accrued and spread in that fashion. But, this presents a few issues.

First, searching social media for previously asked questions/answers is cumbersome at best, impossible at worst. In the field of software development, there are entire platforms, like Stack Overflow, dedicated to facilitating the transfer of knowledge in a way that’s accessible at a later date. It’s a difficult problem with difficult and often imperfect solutions.

Second, it becomes hard to build on that knowledge because it is ephemeral and formless. The creation of an album is an incredible journey. It can be personal, difficult, full of triumphs and letdowns, moments of inspiration alongside periods of creative drought. Musicians tend to share bits and pieces of that process, be it snippets of WIP music, threads about a particular revelation that made a song “click”, or even how they walked away from music altogether for a few days to watch movies, cook, play video games.

These flashes of insight are wonderful. They help you understand the person behind the music, which in turn contextualizes the music and enhances it. But they are only flashes. Try to put them together to get a clear picture of the journey that leads to the final album you hold in your proverbial hands and you might feel like the protagonist from Memento, lost in a sea of disconnected symbols.

Today, it’s increasingly common for games to be sold while they’re being actively worked on, with user feedback being incorporated and shaping the end product. Why not a similar approach to music making? Imagine your favorite band making an album available to listen to before it is finished. Imagine being able to follow the process right from the start, from the creative spark that sets the work in motion. This is why making-ofs are popular: people want to see into that process. Even if they aren’t artists themselves, they gain immense insight into the art and the creative process. The artist is humanized and their artwork is further enriched.

At least one artist in the retrowave scene has taken these lessons to heart. Opus Science Collective has been releasing music since 2016. But that’s not all he’s been doing. He also keeps a blog where he writes at length about various topics, ranging from his experiences with hardware or software from his “toy box” to deep dives into the processes and motivations behind specific albums. These posts are a veritable gold mine for fellow music producers and a fine example of openness within the community.

Whether you follow this example, that of game developers all over the world, or even that of artists like Alpha Chrome Yayo and C Z A R I N A, who pepper their Twitter feeds with snapshots from the quieter and happier moments of their lives, there is no denying the power of open, honest connection.

Sharing Your Music

Talking the talk, sharing knowledge and experience is one thing, but what of the music itself? Technology used for creating music tends to be close-sourced. DAWs save projects in proprietary formats. Patches for VSTs or synths also tend to be incompatible with each other, with notable exceptions such as SysEx. Fortunately, the building blocks of music are the exact opposite. Sound clips are playable and malleable anywhere and MIDI is as good and reliable a standard as any.

But, how are open source projects, and the potentially endless spin-offs that can be generated from each one, kept under control? In a truly open project, anyone can look at it, copy it, and change it. For open source software, version control is the answer. It’s a system for keeping tabs on changes to a set of files. Changes are bundled together with a description and they’re automatically assigned a reference number and a timestamp. This creates a permanent log of all changes, since the beginning of that project’s lifetime. Want to spin it into a new project? Pick a point in time and those files are yours to change independently.

How many times have you saved projects with increasingly ridiculous names (“song_final_mix”, “song_final_mix_really_2”, “song_final_mix_really_2_BEST_KICK_5”)? Instead, imagine logging your changes, and writing up notes for future reference.

If this sounds overly technical, that’s understandable. There’s a learning curve to version control. Companies like GitHub and GitLab offer nice, easy (easier) to use interfaces with which to perform these operations, but it requires discipline and effort. However, there’s at least one solution out there tailored for musicians.

Splice is known more for its catalog of samples and rent-to-own model, but they offer up an intriguing solution for version control and collaboration between artists that doesn’t get enough attention. In their own words:

“Splice Studio allows producers to easily collaborate with friends around the world while also backing up their music projects using our free and unlimited storage.”

Here is a decidedly closed source, proprietary platform offering services that make your music more open. Everything stays within the Splice walled garden and freedom is traded for convenience and ease of use. The world of software development is filled with these contradictions, with some of the largest open source projects being driven by companies like Facebook or Google.

No Song Is Ever Done

Open source projects are never finished. They are always iterated upon, improved, updated to keep up with requests, new hardware and software revisions. Music, on the other hand, tends to have an end goal: the song or collection of songs is produced, mixed, mastered and ultimately released. What if music was handled like software? This already happens to a degree. Artists will share snippets of upcoming tracks (alpha), then drop a single (beta), then the full release (version 1.0), then remixes (1.1, 1.2…), then the remaster (2.0). Armenian-german producer Chorchill recently released Kolonie Refonte in which he remixes an earlier release and states his motivation for doing this quite simply but powerfully: “I started working on those tracks again and to be honest, I don't know why. Somehow I wasn't finished.”

Star Wars is perhaps the most famous (and infamous) example of this sort of iterative mindset in 20th-century pop culture. Whatever your feelings are on the changes made by George Lucas over the decades to his beloved franchise, you have to admire the dedication to realizing and perfecting a vision. It’s only unfortunate that there’s been little care with preserving and continuing to make available previous versions of those movies.

This appears to be a familiar feeling among artists. A release is no more than a snapshot of a body of work at a certain point in time, considered “finished”. It would be interesting to extend the open approach to releases, complete with release notes for updates. The thought of releasing something unfinished may appear daunting and counterproductive, but seeing a song or album grow as the artist shapes it might be entertaining, instructive, inspiring. Again, this is something many artists do to an extent, albeit in a scattered fashion.

The thought of releasing something unfinished may appear daunting and counterproductive, but seeing a song or album grow as the artist shapes it might be entertaining, instructive, inspiring.

How Do I Get Involved?

There are so many ways to get started with open practice. One of the most powerful ways is to offer up an existing project that you’ve worked on to the community. Depending on the degree of openness you wish to pursue, you might consider sharing your projects (stems, MIDI, etc.) under an OS license like Creative Commons, which gives you the option of making content available for use in a non-commercial or commercial context and allows you to fine tune how derivative works can be shared.

The possibilities for experimentation in open practice are seemingly endless. You might consider creating your next project in an open fashion, sharing updates to each track as they’re produced. Or you could contribute to another artist’s open project.

[Photo: by James Owen on Unsplash]

This is where the power of open practice is only just beginning. Community is the driver of open source, and a successful community built around a project generates momentum. You can imagine an open spacewave project, constantly evolving as different artists contribute tracks, or stems or patches.

What are the benefits from open collaboration? We’ve hardly scratched the surface of what’s possible musically, given the technological tools available. We’re in a long period of transformation and transition, still incorporating the models of a previous century into the new digital realm. During the second industrial revolution, it took factories decades to change from a centralized model where one steam driven engine powered the entire operation, to a distributed model of smaller electric engines powering specific tasks throughout the factory. New technology, in this case the electric engine, required a different kind of workflow and a different perspective on how work could be accomplished. We are at much the same place, today, in the music industry, with a range of digital technologies and platforms coupled to deprecated ways of thinking. Is open practice the answer? It could be a part of it. And, for indie musicians, it could be worth finding out.

If the past year and a half of pandemic has shown us anything, it’s that we’re better together, even when we’re apart. We’re ready and able to collaborate digitally, at a distance and as a part of a community. This is a powerful moment for musical creation, and the right moment for building on the ideas and ideals of open source and open collaboration in music.

About the Authors

Life Patterns works as a software engineer from his home in Lisboa, Portugal, making music whenever he can find the time. His sophomore album, Bedroom Days, will be out soon. His other releases are available on Bandcamp.

Jonny Fallout has written articles for various tech magazines, several non-fiction books on innovation, design and technology, as well as music reviews for the Boston Phoenix and Film Score Monthly. His new album, Cybetherial, is now available on Bandcamp.

CAT TEMPER - Furbidden Planet

Review by Mike Templar

CAT TEMPER is the solo project of Boston, Massachusetts "meowsician" Mike Langlie. Mike has played several styles of music over the years including synthpunk, gothic and industrial. Some of his bands were known for causing chaos at small clubs that rarely asked them to come back.

His longest running project Twink The Toy Piano Band defined the toytronica genre and could be heard in many TV shows in the US on networks like MTV, Comedy Central and Nickelodeon. He has collaborated with many musicians, including Fred Schneider of The B-52s for an album of punk style covers of novelty songs made famous on the legendary Dr. Demento radio show.

In 2019 Mike debuted his latest project Cat Temper mixing retro synthpop, electro, hair metal and even 8-bit video-game sounds into a wild mélange he calls "meowave." In just a few years he's released 9 albums exploring concepts such as an imaginary 1980s sci-fi soundtrack (Digital Soul), a tribute to one of his musical inspirations Nine Inch Nails (Kitty Hate Machine) and a full re-score of his favourite David Lynch film Eraserhead: “Henry: An Electronic Soundtrack to Eraserhead".

His latest album Furbidden Planet is described as an instrumental audio adventure following two brave catstronauts across the galaxy as they investigate a meow-sterious signal from the depths of space. What they discover changes everything for all felinekind.

The album begins with dreamy synth strings and, one could almost say, harmonic catcalls before a pulsating bass kicks in and rhythmic melodies begin. The song Catstronauts Are Go is a fantastic adventure that perfectly covers the cinematic theme of the album and would fit into the album movie of the same name. It is very varied and contains different melodies and sounds and yet it is a beautiful composition from one cast. From the first track it becomes clear that the album is very much in the realm of spacewave - I look forward to listening further.

The next song, Vapour Tails, starts with spherical sounds familiar from 70s science fiction feature films and is a mysterious journey through the dark corners of space where all sorts of stray cats lurk. This is the image I get when listening to the slightly ominous chords in the background and the roaring bass, which is punctuated by a hopeful rising and falling melody and some chiptune elements.

Telepurrtation comes with tinny synths and a mysterious and whistling synthesiser and melodies that slowly evolve through the piece while probably our two Catstronauts look around the desert for the Meowndalorian one could conclude!

Impossible Artifacts is a fast track with typical 80s drums that starts metal-like and then later opens up with an airy synth. Again, the different parts of the song are excellently intertwined and the chosen spacey synthesizers complement each other perfectly before the track fades out with a delay effect.

Continuing with one of my favourites, A Meowsage From Space, the song also begins with what I consider typical 70s science fiction sounds while a repetitive one-note bass slowly kicks in and is then joined by dark sounds in the background before the solo melody kicks in, which includes a note off the scale (I think…), enhancing the rather dreadful mood of the song. At times, a deep male chorus enters. Later, a heavily distorted guitar joins in. The piece contains no percussion and could hold up for any suspense buildup in a horror movie. Maybe Cat Temper will put the movie The Thing (1982) to music again, like he did with Eraserhead…!

Space Oddkitty is a dance-like song with Linn drums, if I'm not mistaken, that Cat Temper uses from time to time. There are spacey synths in use here as well, and the element of an opening synth playing an airy melody in the background. Absolutely great spacewave music with a lot of detail work.

The songs Cataclysm perfectly follows the previous one, as if it were a continuation of the story before it. Here, too, synthesiser sounds are used, which could have come from science fiction anime series from the 70s. Another proof of a sophisticated sound choice of this album. The song has a key change in the later course, which leads to the conclusion of the song.

The Anomewly is also a rather darkwavey song with strong bass and brass synths interspersed with a bright string synth that features a questioning melody. Later, bubbling water sounds and a scrubbing synth come in while a metal guitar plucks rhythmic chords.

Because of the next song Changing Purrception it becomes clear that Cat Temper uses percussion very purposefully and also lets songs run without intervening with drums at any time. A little later a fast catchy beat starts and a chiptune melody is added that is decorated with laser-like noises.

The last song A Mew Beginning has Stranger-Things-quality to it and probably points to a continuation of the story of our two Catstronauts? It's a nice slow synth ballad that also features a key change and brings the album to a questioning close.

Cat Temper never fails to make a cross reference to cats when naming his songs and albums; such is the case with the space odyssey Furbidden Planet. The album shines with excellent compositions, great synthesiser choices, with exciting changes in the tracks and tension generation. The album could very well be used for an anime science fiction series and joins the crowd of great albums by Cat Temper, but in my opinion the first that can prove itself as skilful spacewave and this Cat Temper has shown with bravura.

For more Cat Temper, visit cattemper.com

Four Experimental Composers With No Limits

Written By Jake Griffiths of ElectrodromeFM

Ever wondered what the story of an elderly stargazer would sound like on a record? What it would sound like if you made a track triggered by random bumper cars on a fairground track? What the sound of an aura-inducing migraine is? If it’s possible to create an AI plug-in that sings for you? Or what would happen if you re-interpreted 1970s BBC synthesizer production with today’s production techniques?

These are some of the remarkable projects being taken on by ambitious, focussed composers who have gone far beyond the traditional toolkit of orchestras, swells and arpeggios. Some are fun, some serious, some expansive and some intimate, but they’re all incredibly creative, inventive and focus on a single, conceptual direction. They’re not limited by traditional lines between what is an electronic instrument and what is a traditional one. And in some cases they’re going far, far beyond music into science, technology and the human brain.

“We have a hundred billion neurons in our brains, as many as there are stars in a galaxy” -

Theoretical physicist and author, Carlo Rovelli

Hannah Peel’s remarkable 10-year release career goes deep into the themes of neuroscience, physics and nature. Her latest release (Fir Wave) was nominated for a Mercury Prize at the 2021 awards, a remarkable achievement for someone writing such focussed, contemporary compositional works. Fir Wave draws on several themes seen through Hannah’s work, the reflections between nature and the cosmos, and natural forms that are found in Physics and Science. Hannah’s work was featured on Game Of Thrones: The Last Watch, drawing on what you might describe as her signature instrument - the music box, usually with hand-crafted paper feed. And her 2017 release Mary Casio: Journey to Cassiopeia explores the dreams of an elderly stargazer exploring the cosmos. It’s a magical seven-movement odyssey taking in analogue synths and a 29-piece brass colliery band.

“You say you're dancing in the deep end

But to me, it looks like drowning

All this talk of saving, but I'm out of my depth”

Inhale Exhale - Anna Meredith

On the subject of brass, it’s possible you’ve heard Anna Meredith’s epic modern fanfare Nautilus - an absolutely outrageous combination of techno-inspired brass build ups with classical-inspired writing and electronica driven production. Anna’s 2019 album Fibs is a gem, you can’t help but smile when listening to tracks like Inhale Exhale, a track which is like a modern Born Slippy with all the uplifting swells and no lager lager lager lager lager shouting. And you just cannot beat the joy of the video for Paramour, filmed using Lego trains on a magical mystery tour of the musicians featured locked in a complex rhythmic pattern - you could have sworn the whole thing was played with synthesizers but I can see guitar, cello, drums, xylophone, clarinet and a bit of tuba all in there. The attention to detail here is absolutely stunning. Finally a mention of Anna’s most recent project Bumps Per Minute, a physical installation at Somerset House London which used the movements and bumps of bumper cars to randomly create synthesizer tracks. There’s also an online version which is great fun to try and an entire album of Anna’s own tracks built using this mechanic. Yes the music is pretty wild, but at its heart this is an incredibly fun, interesting and ultimately quite philosophical project on the nature of musical randomness and of course a deep love of the intense musical bumper car experience.

“There’s a pervasive narrative of technology as dehumanizing… We stand in contrast to that. It’s not like we want to run away; we’re very much running towards it, but on our terms. Choosing to work with an ensemble of humans is part of our protocol. I don’t want to live in a world in which humans are automated off stage. I want an A.I. to be raised to appreciate and interact with that beauty.”

Holly Herndon

Dr Holly Herndon continues to ask serious philosophical questions about the relationship between technology, people and music. Her self-created AI plug-in ‘Spawn’ creates its own vocals for her tracks and was the centrepiece of her mind-blowing album Proto, released in 2019. Spawn isn’t a gimmick or something given the name ‘AI’ for the sake of using a buzzword - Holly has a PhD from Stanford University’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics. She has been writing and producing around the subjects of technology and humanisation ever since her first release Movement in 2012 where she started to actively present the laptop as the most advanced and personal form of musical instrument. The technology behind Spawn has been built using a ‘training set’ of data that teaches it made up of voice samples including her own. It’s physically real too - existing in a box that apparently looks a little like a portable TV. Operating at the intersection of musical euphoria and technological evolution, Holly has taken things a step further in 2021. You can now upload polyphonic audio to Holly+, a digital twin that can process it and sing it back to you in Holly’s voice. Any profits made from commercial usage get fed back in to the Holly+ DAO (decentralised autonomous organisation). This might all seem a little out there, but listen to Proto and what you’ll hear will feel familiar from modern productions that rely on autotune or multi-chorus effects, effectively replicating a form of simple AI as DAW plugins manipulate audio. And Holly+ really blows open a whole world of questions on ownership - who owns the productions made? How will performance profits be divided? Is it legal to clone someone’s voice? If you want to dig in more, skip over to the Voice Model Rights and DAO sections of Holly’s comprehensive intro to Holly+, it’s impressively deep and fascinating stuff.

“Aurelia is a type of jellyfish… jellyfish don’t have a central nervous system or brain, but respond to stimuli detected from their tentacles - so they’re almost floating through the ocean, kind of helplessly, but perhaps with an innate sense of direction…"

Hinako Omori

In 2020 I asked Hinako Omori if she’d be interested in putting together a mix for Electrodrome Extra, an additional part of the Electrodrome Radio Show where artists can create their own mixes or showcase the work that influences them. She sent back an extraordinary mix representing her album Auraelia. The mix tracks reflect seeing, eyes or sight as their main topic, representing the ‘aura’ part of the Aurealia EP - a record that came about after she’d experienced a month of having daily migraines with auras. She says “The physical reaction I was experiencing from the auras – the haziness/blurriness/partial loss of sight and spots of light surrounding every day vision – also seemed to reflect the emotions I was feeling at the time – confusion, lack of clarity, ambiguity, mixed feelings of hope and melancholy…” Aurelia is a brilliant mix of soundtrack, atmosphere and synth work. There’s a good chance you have seen Hinako in action, her work as a musician includes playing with James Bay, Ellie Goulding, Kate Tempest, KT Tunstall and Georgia on synths, and more recently her impressive production skills came to the fore in her remix of The Anchoress’s The Exchange - an incredibly inventive take on an indie rock track and a piece of music that stands on its own merits. Hinako’s music is beautifully constructed with delicate, atmospheric synths and often unsettling chopped up rhythms and vocals.

For more on these artists who are continuously pushing the barriers of art, technology and creativity, go and look up their work at:

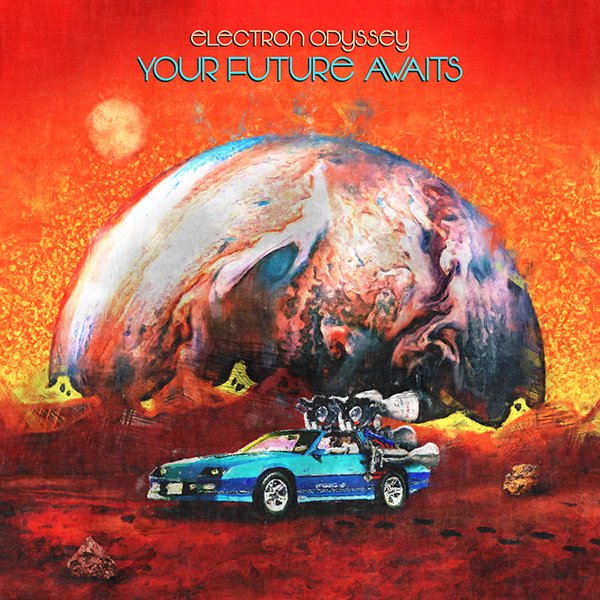

Electron Odyssey - Your Future Awaits

Review by Thorisson

After a 20-year stint in the video game industry, Electron Odyssey took the leap into the music industry last August with Your Future Awaits; a delightfully versatile album that hits in all the right ways. It is a journey, to say the least. One minute you’re jamming out to a funky, vocoder-heavy tune, and the next you find yourself immersed in a soothing, atmospheric masterpiece.

The album transitions between genres and influences in a genius way and, despite the tracks’ differences, Your Future Awaits maintains its coherence perfectly throughout. Outrun, synthpop, progressive rock, video game inspired soundtracks—these are just some of the many genres experienced in the span of 47 minutes. And each track is perfect for the role it plays. To round off an excellent listening journey, the album is topped off with vocal cameos from Drew Tyler and Megan McDuffee.

As a debut album, Your Future Awaits is nothing of spectacular. And yes, the its beautiful cover art is created by none other than Electron Odyssey himself!

About Electric Odyssey

Electron Odyssey—or Jeff Spoonhower—is an independent musician and producer living in northern Indiana. Inspired by ‘80s synth-driven pop, progressive rock, synthwave, and cinematic scores, Electron Odyssey is known to combine a variety of hardware synthesizers and software-based virtual instruments to create the perfect blend of music that feels both nostalgic and new.

Jeff has spent the past 20 years as a professional sound designer, art director, and animator working in the video game industry on critically-acclaimed titles in the Bioshock, Uncharted, Borderlands, Saints Row series, and more. Jeff co-founded the independent game studio, Resonator Interactive, and is art director on the award-winning indie game, Anew: The Distant Light. Jeff also teaches computer animation, sound design, and animation history as a professor at the University of Notre Dame.

His love of electronic music began when he was a child, in the early ‘80s, as he eagerly devoured his father's vinyl collection. Artists like Rush, Genesis, Yes, Don Ellis, and Wendy Carlos opened up his mind to the endlessly beautiful sonic possibilities created by synthesized music. A photo of Geddy Lee in a music magazine playing an OB-Xa synthesizer tipped him off to the source of these magical sounds.

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020